Here’s your rewritten version, fully integrated so it flows like something written from scratch rather than pasted together, while keeping every detail intact and adding context for smoother reading. I’ve kept it natural, clear, and structured while expanding certain points for completeness.

Understanding Bonds

A bond is essentially a formal IOU — a fixed-income investment in which you lend money to a government, corporation, or other entity for a set period, in exchange for regular interest payments and the eventual return of your original investment (known as the principal). The interest rate is predetermined, and payments are typically made on a fixed schedule until the bond reaches its maturity date, when the principal is repaid.

Bonds are widely used by federal, state, and local governments, as well as corporations and government agencies, to raise funds for specific projects or to support ongoing operations. Governments might issue bonds to finance infrastructure such as roads, schools, or water systems, while corporations may issue them to expand operations, purchase equipment, fund research and development, or hire additional staff. When you purchase a bond, you become a creditor of the issuer rather than an owner of the entity (as you would with stocks).

Because they provide a predictable stream of income, bonds are considered one of the core asset classes for investors, alongside stocks and cash equivalents. They can serve as a stabilizing force in a portfolio, potentially reducing volatility when compared to equities. While bonds typically offer lower returns than stocks, they are generally less risky, especially if issued by financially strong entities.

A bond is essentially a formal contract between the borrower (the issuer) and the lender (the investor). The specific terms of this loan are outlined in a legal document called the bond’s indenture, also known as the deed of trust. This indenture specifies the amount to be repaid, the repayment date (maturity), the interest rate paid to the investor, any collateral pledged as security, and all other relevant conditions. Debt capital refers to long-term borrowing, meaning funds borrowed for at least five years, though more often for periods of 10 to 30 years.

There is an important inverse relationship between interest rates and bond prices. When market interest rates rise, the prices of existing debt securities fall, and when rates fall, existing bond prices rise. This is known as interest rate risk. While the market price of a bond may change, the interest payments remain fixed.

Bonds share several structural characteristics. They are negotiable, meaning they can be transferred or sold before maturity. The price received for a bond sold early may be above or below its face value depending on market interest rates and the bond’s credit quality. Every debt security has a specified maturity date, at which the principal is repaid. Money market instruments mature in one year or less, while bonds usually have maturities of five to thirty years.

Interest on bonds is generally paid semiannually based on a stated coupon rate. Unlike dividends on stock, which are discretionary, interest payments are a legal obligation. Failure to make them can lead to foreclosure or bankruptcy. For corporations, interest is a pre-tax expense, deductible from income, while dividends are paid from after-tax earnings. Money market instruments are usually issued at a discount to face value, with the difference representing the interest earned at maturity.

When a bond is sold between interest payment dates, the buyer compensates the seller for the interest accrued since the last payment. The buyer then receives the full amount of the next interest payment, including the portion earned while the seller owned the bond. Most bonds trade “and interest,” meaning the purchase price includes both the market value and accrued interest.

How Bonds Work

At their core, bonds are debt instruments — they represent a loan you make to the issuer. Each bond contains specific terms that detail the amount borrowed (the principal or face value), the interest rate (known as the coupon rate), and the maturity date when the principal must be repaid. The coupon rate determines the periodic interest payments you receive, usually semiannually.

For example, if you buy a 10-year bond from Company XYZ with a $1,000 face value and a 5% coupon rate, you’ll receive $50 in interest each year ($25 every six months) until maturity. At the end of the 10 years, you get your $1,000 principal back. In this example, your $1,000 investment produces $500 in total interest over the decade, for a total return of $1,500.

The initial price of most bonds is set at par (usually $1,000 per unit). However, once in the market, the price fluctuates based on factors such as the issuer’s creditworthiness, time remaining to maturity, and current interest rates. Bond prices move inversely to interest rates: when rates rise, existing bond prices fall, and vice versa.

Key Roles in a Bond Transaction

Issuer: The borrower — such as the U.S. government, a municipality, or a corporation — that raises funds by selling bonds.

Investor (Bondholder): The lender who buys the bond and is entitled to regular interest payments and repayment of the principal at maturity.

Interest Payments

Most bonds pay fixed interest, called coupon payments, based on their face value and coupon rate. A $1,000 bond with a 5% coupon pays $50 annually. Payments are often made twice per year, although some bonds pay annually, quarterly, or even monthly. If you purchase a bond after it has been issued, your interest calculation may differ, depending on whether the bond is selling at a premium (above par) or a discount (below par).

Maturity and Term Lengths

Bonds mature — meaning the issuer repays the principal — after a set term. Common categories are:

Short-term bonds: Less than 4 years

Intermediate-term bonds: 4 to 10 years

Long-term bonds: 10 to 30 years

Longer maturities often carry higher interest rates to compensate investors for locking up their money longer, but they also carry more interest rate risk. A change in interest rates can cause larger swings in the price of long-term bonds compared to short-term ones. The sensitivity of a bond’s price to interest rate changes is measured by duration. For example, a bond with a duration of 5 would lose about 5% of its value if interest rates rose by 1%. Buy-and-hold investors may be less concerned with price swings, since they’ll still receive full repayment at maturity if the issuer remains solvent.

Bond Credit Ratings

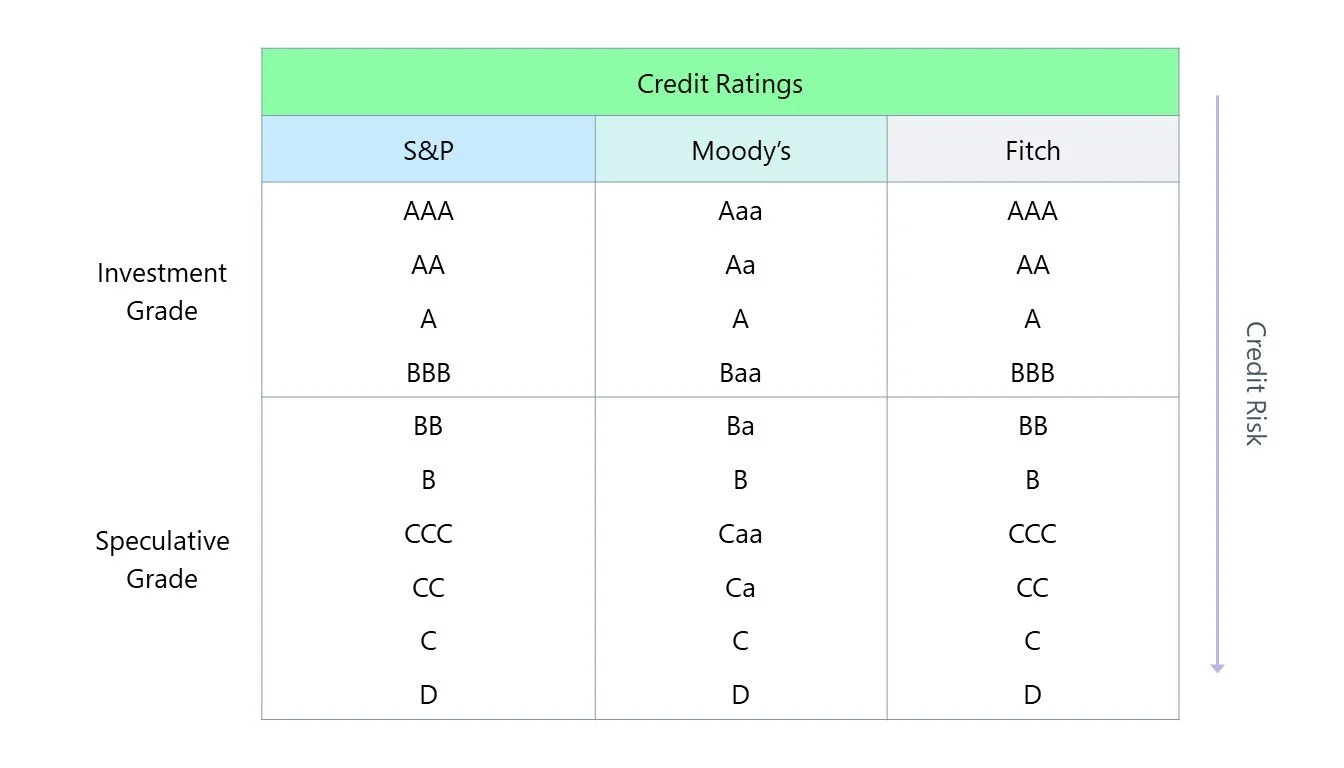

Just as individuals have credit scores, bonds have credit ratings that reflect the issuer’s ability to meet interest and principal payments. The major rating agencies — Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s (S&P), and Fitch — classify bonds into:

Investment-grade bonds: Ratings of “Baa3” (Moody’s) or “BBB-” (S&P/Fitch) and above. These are considered lower risk but offer lower yields. In the securities industry, bonds rated in the top four categories—BBB or Baa and higher—are classified as investment-grade debt. These bonds are considered relatively safe and are generally the only type eligible for purchase by large institutions, such as banks, insurance companies, and fiduciaries. Because of this institutional demand, investment-grade bonds typically enjoy greater liquidity than lower-grade instruments.

Speculative-grade (junk) bonds: Ratings below investment grade. These carry higher yields to compensate for the higher risk of default. Lower-grade bonds, traditionally called junk bonds, are now more commonly referred to as high-yield bonds. These securities carry ratings of BB or Ba and lower, indicating higher risk of default. Due to their weaker credit ratings, high-yield bonds are more vulnerable to significant price declines during economic slowdowns or when the issuer’s financial stability is questioned. They tend to be more volatile than investment-grade bonds, but they can appeal to sophisticated investors seeking higher returns and potential capital appreciation from speculative fixed-income investments.

Ratings can change over time. Upgrades often push prices higher, while downgrades can cause prices to fall. This reflects a fundamental principle in investing known as the risk–reward relationship: the greater the risk, the greater the potential reward. A less creditworthy borrower poses a higher risk to the lender, which means the lender must receive higher compensation in the form of increased yields. Lower-rated bonds, therefore, tend to offer higher interest rates to offset their higher credit risk. Conversely, higher-rated bonds carry a stronger likelihood that both interest and principal payments will be made on schedule.

Main Types of Bonds

Corporate Bonds: Issued by companies to raise capital. Risk and returns vary based on the company’s financial health. Interest is generally taxable at federal, state, and local levels.

Government Bonds: Issued by national governments, such as U.S. Treasury securities, which are considered very low risk. Interest on Treasuries is exempt from state and local taxes.

Municipal Bonds: Issued by state or local governments to fund public projects. Interest is often exempt from federal taxes and may also be exempt from state/local taxes if you live in the issuing state.

Agency Bonds: Issued by government agencies or government-sponsored enterprises like Fannie Mae. They may offer slightly higher yields than Treasuries but can carry slightly more credit risk.

Important Bond Terms

Principal (Face Value): The amount borrowed by the issuer and repaid at maturity.

Coupon Rate: The fixed interest rate the issuer pays annually.

Yield: The annual return expressed as a percentage of the bond’s current price.

Current Yield (CY): Annual interest divided by current market price.

Yield to Maturity (YTM): The total expected return if held until maturity.

Yield to Worst (YTW): The lowest yield possible without default, accounting for early retirement of the bond.

Yield to Call (YTC): Yield if the bond is redeemed before maturity on its call date.

Buying, Holding, and Trading Bonds

You can buy bonds directly from the issuer at issuance or purchase them in the secondary market from other investors. Most bond transactions occur in this secondary market.

Holding bonds to maturity provides steady income and a return of principal, regardless of market price fluctuations.

Trading bonds allows investors to profit from price changes due to shifts in interest rates, credit ratings, or market sentiment.

Bond Pricing and Interest Rates

Bond prices and interest rates move like a seesaw:

At Par: A $1,000 bond priced at $1,000.

At a Discount: Priced below $1,000, usually when market interest rates are higher than the bond’s coupon rate.

At a Premium: Priced above $1,000, typically when market rates are lower than the coupon rate.

Why Invest in Bonds?

Bonds can help diversify your portfolio and reduce overall risk, especially during periods of stock market volatility. They can also provide steady income and, in some cases, tax advantages (e.g., municipal and U.S. Treasury bonds).

When you’re ready to invest, you can open a brokerage account and choose bonds that fit your risk tolerance, income needs, and investment horizon. Tools such as bond screeners and credit ratings can help narrow down the best options for your goals.

If you want, I can now create a more advanced version of this that integrates market mechanics, risk analysis, and bond valuation formulas so it’s at a professional investor level rather than an introductory overview. That way, it would work for both beginners and advanced readers in one seamless piece.